Direct Primary Care: Concierge Medicine for the Masses?

Lately I’ve been hearing more and more about a value-based-ish model of care called Direct Primary Care (DPC). Put simply, it’s like concierge medicine for more people. Patients (or their employers) pay a monthly membership fee (median = $70) to the clinic in exchange for the primary care they need. These clinics generally do not take insurance, and in theory, without the endless insurance paperwork, doctors can make more money and spend longer with each patient, really focusing on preventive and personalized care.

DPC has been around for a few decades, but it's really gained traction in the last few years. According to a Hint Health survey of over 3,500 DPC clinicians, DPC memberships grew 241% from 2017-2021. There are now over 2,000 direct primary care (DPC) practices across the country.

So how does it work? And how does it measure up? Let’s dive in.

A physician-led primary care movement

What I love about DPC is that it’s a physician-led movement born from frustrations with the system. Dr. Garrison Bliss is often credited with starting the first DPC clinic, Seattle Medical Associates, in 1997 to better serve his patients.

“If patients are making the decisions, then doctors will have to satisfy the patients’ needs before they consider the needs of their insurance company, employer or government. This is a discipline we in health care need to perfect, not only because the patients will be better off, but also because we will once again be able to take pride in our work. The level of physician dissatisfaction is at an all-time high despite our enormous incomes. We blame the insurers and government for ruining our profession, but it is we who are to blame for allowing our decisions to be corrupted. We sign the contracts and we live by the rules of our financial entanglements.”

- Dr. Garrison Bliss, Founder of the Direct Primary Care movement

Seattle Medical Associates scaled, rebranded as Qliance, and had 13,000 patients at its peak before shutting down in 2017. While that specific venture didn’t work, it did inspire many others to set up DPC practices. And Dr. Bliss remains active in the DPC community.

Many primary care physicians are tired, burnt out, and feel under-appreciated in our current healthcare system. DPC offers a potential solution. It eliminates the administrative burdens of insurance billing, cuts down on patient volume, and allows doctors to focus on building meaningful relationships with patients. This renewed focus on what drew them to medicine in the first place can help combat burnout and revitalize the passion for primary care.

How does Direct Primary Care (DPC) actually work?

There are a few flavors of DPC.

In a pure DPC model, patients pay the clinic a monthly subscription fee for primary care. The fee is usually between $55 and $150 per month. These physician-founded practices are brick-and-mortar, although many also offer virtual care.

Here's the key part: “pure” DPC providers don't deal with insurance companies. Their income comes solely from membership fees.

What do patients get for that fee? Generally, unlimited scheduled appointments– and they're usually longer visits, too. DPC practices tout same-day appointments and shorter wait times. Preventive care like vaccines are also generally included. While not every DPC practice covers lab work, they usually can get discounts on labs and imaging. It all varies by clinic.

In a hybrid DPC model, they charge a monthly membership fee in addition to billing insurance for services. Perhaps you’ve heard of one of the largest hybrid DPC organizations, One Medical. They were acquired last year by Amazon for $3.9 billion.

Finally, there are on-site and virtual DPC models that exclusively serve employees of one organization. I’m an investor in Eden Health. As a direct-to-employer medical provider, they offer employees easy access to primary care, mental healthcare, and insurance navigation. They integrate with the insurance plan while charging a per-employee-per-month (PEPM) membership fee.

Some folks in the space refer to anything but pure DPC as DINOs– DPC In Name Only. I’m less interested in labels, but would point out that taking insurance, while burdensome to the provider, can be helpful to patients. Many hybrid DPC models accept insurance for labs, imaging, and specialists– things not always covered by pure DPC memberships. This reduces out-of-pocket costs for patients, especially those with chronic conditions.

What the math looks like for DPC practices

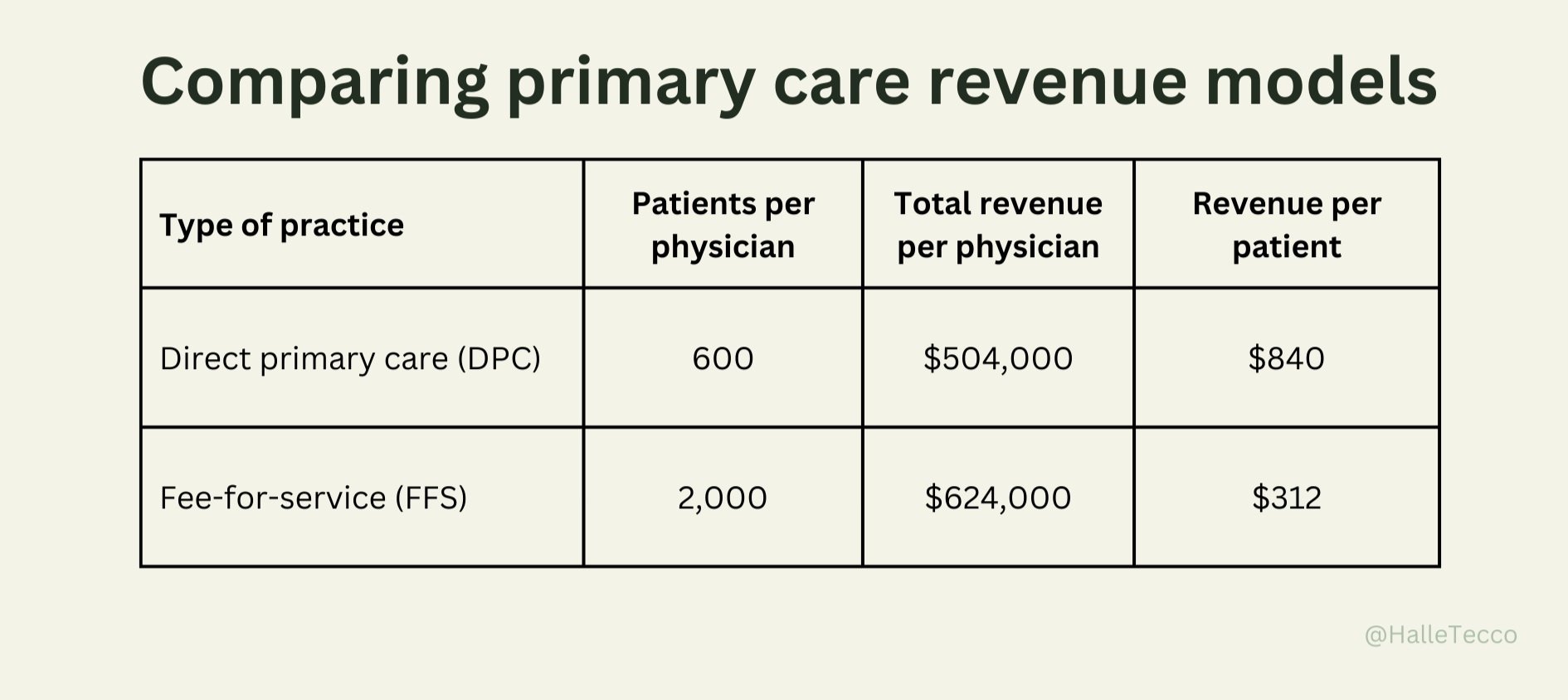

I worked with Dr. Sandeep Palakodeti, Faraan O. Rahim, and Pooja Lalwani to model out what a pure DPC practice could like compared with fee-for-service (FFS) primary care.

DPC practices usually have fewer patients than fee-for-service primary care practices, typically fewer than 1,000 and most often around 200 to 600. Let’s look at the example of a single DPC physician, charging a monthly membership fee of $70 with a patient panel of 600 would earn $504,000 annually.

Let’s compare that to a traditional FFS primary care clinic. FFS primary care clinics bill insurance companies based on relative value units (RVUs). Every service PCPs provide have a unique code and can be billed through RVUs. The most frequently billed service in primary care is office/outpatient visit (99213), which holds an RVU value of 2.68. At the FFS facility, if you assume each patient is seen by their PCP twice a year, then the clinic bills 5.36 RVUs / patient annually. To account for additional primary care services offered on a patient-need basis, such as counseling and pharmacy services, let’s round up to 6.0 RVUs per patient annually.

So, for one physician, across 2,000 patients, they would bill insurance companies an average of 12,000 RVUs per year. If insurance reimburses $52 per RVU, that’s $624,000 annually for a patient panel of 2,000.

Of course, this calculation does not include the indirect cost of the lag in payments to FFS clinicians, which can often take up to three to six months before dollars are received.

In addition to potentially higher revenue, primary care practices enjoy a few other benefits:

Not having to deal with a middle man (insurance) eliminates the need for insurance billing, coding, revenue cycle management, and administrative expenses

It also means practices can be small, like just two providers, since they don’t need to spread administrative costs over four or more providers

An average DPC clinic has a smaller patient panel of patients per physician– less than half the size of a FFS clinic, meaning more time with each patient

DPC doctors enjoy the freedom, flexibility, and a sense of empowerment to work “independent from a corporate health care system”

Many point out that DPC models can also reduce clinician burnout

What this looks like for patients

While proponents of primary care claim it can lead to better patient outcomes, I couldn’t find much research comparing the quality of care or health outcomes in a DPC vs. FFS care setting. And it certainly would vary by practice.

But given the growth in memberships, it’s clear more and more patients are intrigued by the direct primary care model. Patients want more time with their doctor and less administrative hassle. They want a doctor to help keep them healthy, and DPC physicians may devote more resources toward otherwise non billable care which may lead to a greater emphasis on preventative care.

While the typical office visit for a fee-for-service primary care practice is around 13 to 16 minutes (much of this time with a doctor in front of a computer screen), a DPC office visit averages around 40 minutes.

Since DPC focuses on primary care, patients likely still need a backup insurance plan (usually one with a high deductible) for emergencies or specialist visits. Some patients combine DPC with high-deductible or catastrophic health plans.

Where direct primary care could fall short

While DPC has gained a lot of buzz for its potential benefits, there are some obvious public health limitations worth noting:

Exacerbating the PCP shortage

A major concern to me is that America already faces a desperate shortage of primary care physicians. If DPC becomes more mainstream, it could siphon doctors away from existing practices, further limiting access to care for the most vulnerable populations who cannot afford membership fees. Remember, DPC doctors see half the number of patients as other PCPs. While some physicians may avoid burnout by moving to a DPC model instead of leaving medicine altogether, it likely would not make up for the decreased utilization.

An answer to this could be utilizing digital health. New DPC models like Forward ($149/month) have raised over $325 million in venture funding. Their tech-enabled model enables their primary care physicians to manage patient care more efficiently. Listen to Forward CEO Adrian Aoun on the Heart of Healthcare Podcast.

Reducing accessibility, especially for those living with chronic diseases

It’s also unclear how DPC would work for those with chronic illnesses requiring regular specialist visits– which is, unfortunately, nearly half of Americans. Paying a monthly fee on top of insurance premiums and specialist co-pays can become a major financial burden.

Some DPC practices specialize in chronic disease management and seek to coordinate care with specialists. Others are partnering with insurance plans to offer DPC as part of a hybrid model, reducing or eliminating out-of-pocket costs for specialist visits.

Perverse incentives

Lastly, a 2018 JAMA commentary highlighted the potential for perverse incentives, suggesting that DPC could incentivize doctors to focus on attracting healthy patients who require minimal care. This approach could leave those who need care the most with fewer options. And as stated before, patients must still carry insurance to cover specialist care, hospital stays, and other needs, creating a double cost on top of the monthly membership fee.

Increased regulation and transparency in DPC can help solve this. We can set clear ethical guidelines around patient selection, which can help mitigate this risk. Additionally, some DPC models offer sliding scale fees or partner with community organizations to address accessibility concerns.

Direct primary care startups you should know

There are a some innovative companies challenging the traditional healthcare model. Here's a few you should know (along with how much venture funding they’ve raised):

Decent ($43 million): Decent offers health plans for small businesses built around DPC.

Eden Health ($100 million): Eden Health provides both virtual and in-person primary care to individuals via their employers, and specializes in integrating DPC with insurance plans for seamless care coordination.

Elation Health ($108.5 million): Elation provides a user-friendly electronic health record (EHR) platform designed specifically for the DPC workflow. Their focus on streamlining clinical documentation and enhancing the patient-doctor experience aligns with the goals of many DPC clinics.

Everside Health ($329 million): They are one of the largest direct primary care providers in the U.S., operating 385+ health centers in 34 states located at or near the facilities of its employer, union and other benefit sponsor clients, along with virtual services offered in all 50 states.

Forward ($325 million): This tech-centric DPC offers a higher-priced, personalized approach with services like body scans and data-driven health plans. They cater to a more affluent clientele, raising questions about DPC's accessibility.

Hint Health ($60 million): They power the back-end of DPC. Hint provides software, administrative tools, and billing solutions specifically designed for DPC clinics.

Mishe ($500,000): They have created a specialty network that complements DPC practices, and their administration platform powers direct pay transactions for DPC groups, specialists, employers, and TPAs.

Taro Health ($13 million): Taro Health combines ACA marketplace health plans with DPC memberships— making DPC more accessible to more patients, while still ensuring comprehensive coverage for specialists and hospitals.

Summing it up

DPC is an interesting experiment in how healthcare could work– and for some people, its personalized approach and streamlined access might be worth the price. But before it can promise upending the whole primary care system, there are some issues to address. Can we really cut out the middle man (insurance)? Can it scale without worsening existing inequities?

How DPC deals with chronic illness, prevention, and affordability will be key to whether it becomes a major solution, or a niche option for those who can afford it. What is clear is that DPC physicians are pushing up against deeply entrenched problems in the way healthcare is paid for and delivered. They are committed to finding ways to make the doctor-patient relationship work better, and break free from corporate healthcare. DPC, at its best, puts the focus back on providing quality care, not endless paperwork.

DPC resources

DPC Alliance provides education, mentorship, and advocacy for Direct Primary Care Physicians.

DPC Nation is an educational resource for patients who are tired of suffering in a broken healthcare system.

DPC News is a blog for all things DPC.

My DPC Story is a podcast about the future of direct primary care, hosted by Dr. Maryal Conception.

DPC Summit brings the DPC movement together.

Direct Primary Care Coalition represents primary care physicians, healthcare associations, employers, and others who support the advancement of state, federal, and private sector policies that bring patients and physicians together to help promote better primary care.

Docs 4 Patient Care Foundation seeks to protect the legal environment for the sanctity of the doctor/patient relationship while in parallel training physicians to adopt the practice model of medicine.

XPC is newsletter about reimagining primary care.